There is a scene at the beginning of Scorsese’s remake of Cape Fear in which the camera tracks through the front door of a suburban home and settles on a close-up of a hand sketching long, bold lines across a pad of newsprint. “The idea is to resolve the tension” the voice over, a women with a slight drawl, assures us, “I need a motif that’s about movement…” (The director revealing his method?) The camera pulls back and Jessica Lange appears, pencil in one hand, cigarette in the other, behind a tilted drawing table. “If you can balance those ideas in a way that’s pleasing to the eye, you’ve got a logo.” That’s right, Jessica Lange just ruminated on the ingredients of a logo.

Design is not the usual fare of Hollywood screenwriters. Type or toasters somehow lack the dramatic possibilities of, say, international espionage or intergalactic crime fighting. Designer appearances in films are, therefore, rather rare occurrences. And except in the most obscure cases, the fact that a character just happens to be a designer is usually incidental to the plot, a fluke, an aberration, the whim of a writer. This rarity makes the occasional sighting all the more thrilling. But as infrequent as they may be, the incidental appearances may still tell us something.

It is commonly accepted that the close examination of the artifacts of popular culture will suggest the way in which that culture regards specific subjects. We can expect, for instance, that class or gender distinctions of a certain society may well be reflected in its films and literature. Even consciously radical work – work that intentionally defies or overturns conventions – tends to be symptomatic of the conditions it rejects.

Films that depict designers as characters, therefore, should divulge some of the meanings and values that designers have in our culture. Character roles are symbolic (i.e. they are a device of the plot) and authors/directors choose symbols that have some resonance. Unfortunately, the sample in this case is tiny; the number of films that feature designer/characters is manageable on two fully fingered hands. This in itself may be a sign of the profound lack of impact designers have had on the popular imagination. But every so often the television and movie universe – populated with slick lawyers, exhausted doctors, gritty cops, sly detectives, hard-boiled journalists, predatory stockbrokers, conniving business executives and heroic athletes – is infiltrated by a more artistic type.

Industrial designers fell in love with Eve Kendall (Eve Marie Saint) the moment she peaked out from under her carefully controlled mascara and murmured, “I’m an industrial designer…” in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. (It is perhaps the only time those words are uttered on the big screen.) The famous lie – she is after all a spy – comes in the middle of her elegant seduction of advertising executive Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant) in the dining car of the Twentieth Century Limited en route to Chicago (setting up one of the campiest sexual metaphors in cinema, a cut from the sleeper compartment of the amorous couple to the locomotive rushing into a tunnel.) Industrial design must have been considered a sufficiently unusual and masculine career for a woman – “twenty six and unmarried” – justifying both her independence (traveling alone) and impertinence (seducing Grant.) There is the added symbolism of the late-fifties affair between design (Saint) and advertising (Grant as Madison Avenue man,) and in the film, as in design history, it is often difficult to figure out just who is screwing whom.

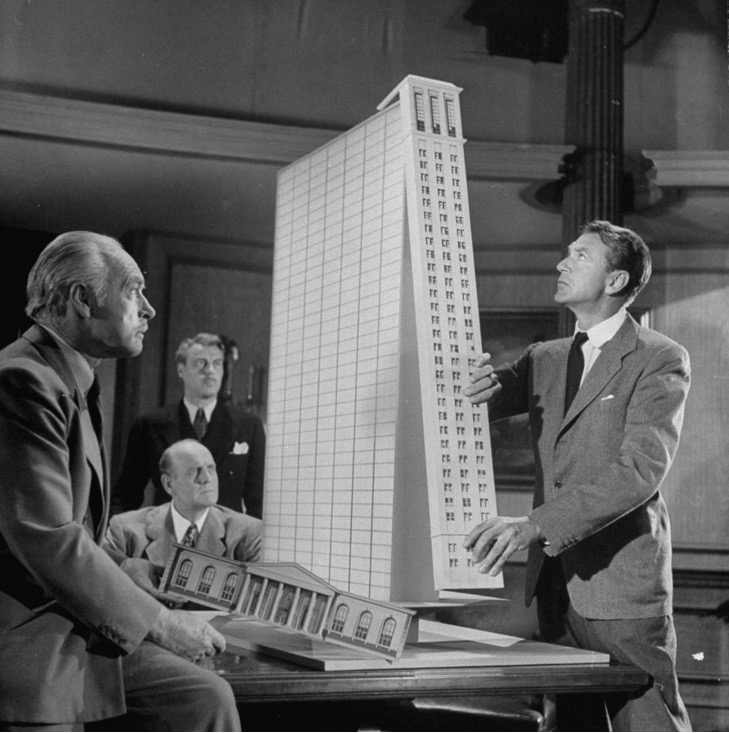

There’s little question of who’s on top in the most famous designer film of them all, King Vidor’s 1949 adaptation of Ayn Rand’s novel The Fountainhead. No other feature film inscribes the popular trope of the lone designer as succinctly. Gary Cooper stands tall (as architect Howard Rourke) against a world of mindless drones and committees of sniveling, compromising, corporate swine. The film, and Rand’s objectivist philosophy, has probably done more to drive disaffected, misunderstood undergraduates into architecture than any other source. “I don’t build to have clients, I have clients so that I can build!” Rourke announces, and you can hear the echo in a thousand design studios and graduate classes across the land.

The Fountainhead is based loosely on the figure of Frank Lloyd Wright. (Warner Studios reportedly offered the set design commission to Wright but balked at his six figure fee.) The Warner set shop did their best to create in the Wright style drawings and models that would be the manifestation of Rourke’s genius. The results were so laughable that architect/industrial designer George Nelson actually critiqued the Hollywood representation of modernist design in a contemporaneous issue of “Interior Design”. Noting that the similarities between Rourke and Wright were “purely intentional and generally unfortunate” Nelson went on to add: “Like all work that is derivative and synthetic, the buildings of Howard Rourke have the fascinating property of presenting all the qualities of the original except the essentials.”<

The Fountainhead ends with Rourke arguing before a jury of his peers his right to dynamite a building that deviated from his exact specifications. “My ideas are my own and no man has a right to them,” he declares, after which the jury bursts into applause and finds him innocent. He’s then commissioned to build the tallest structure on earth with absolute design authority granted contractually, and marries the woman he once raped, the stunning Dominique Francon (Patricia Neal) widow of the billionaire publisher who commissioned the skyscraper… all in the final minutes of the film. The ultimate scene depicts the super-architect, wind in his hair, arms akimbo, astride the mile high tower; Dominique rocketing upward toward him aboard a construction elevator. Things happen fast at the top.

Apparently feeling rather abused by the sniveling, compromising, corporate swine of the film industry, director Francis Ford Coppola made his own version of the stoic loner designer fable. Tucker: A Man and his Dreams depicts the trials and tribulations of Preston Thomas Tucker (Jeff Bridges), a semi-legendary automotive designer from the late forties. Like Rourke, Tucker is despised by the mediocre and the unscrupulous, and is ultimately destroyed by the dark forces of bureaucratic collusion in the form of Big 3 executives and corrupt politicians. Tucker turns on the familiar form of the designer as visionary-dreamer-crackpot, too far out ahead of his time to be understood. (An appealing symbol for Coppola, who was at the time in something of a decade-long slump.) Like Rourke, Tucker finds himself before a jury, arguing his right to dream and fail. Of course he also is also acquitted after an impassioned appeal to his fellow Americans, citizens of the land of opportunity.

Both Tucker and Rourke portray a popular and romantic vision of modern design. Yet there are slight but important distinctions between the two iconoclasts. Rourke defines modern design as an elitist and egomaniacal pursuit, the embodiment of objectivism. Design is an end in itself, a celebration of a single genius’ achievement, removed from moral consequence. Rourke despises the masses. It’s a troubling notion coming on the heels of the the World War. (David Lean’s Bridge Over the River Kwaisuggests another scenario in which design, or at least engineering, is removed from moral consideration. The Japanese army exploits the captive British engineer’s (Alec Guinness) single-minded obsession with solving the problem in isolation of the context. The engineer unwittingly collaborates with the enemy. Recognizing his error, Guinness is compelled to destroy his own creation at the end.)

Tucker, on the other hand, is the populist designer, thinking not only of his dreams but of the good of the common man. He struggles to make his cars safe and affordable. Rourke stands for the rights of the individual, Tucker for the good of the powerless, he’s the image of social responsibility. He represents the other popular notion of the modern designer as the guardian of social welfare. His battle is, in effect, a Papenakian consumer rights campaign aimed at the morally corrupt forces of corporate capitalism that undermine free choice with false innovation.

Designer characters like Rourke and Tucker tend to fulfill one of several highly codified functions. Design can be portrayed as a noble calling, removed from, and beleaguered by, the corrupt circles of corporate America (Tucker and Rourke), or as a superficial obsession to surface detail that obscures more important human relationships.(Dustin Hoffman in Kramer vs Kramer as the creative director too possessed with concerns of his hollow advertising career to see the disintegration of his marriage; Graphic designer Judy Davis as the eighties style yuppie in The New Age.) Architecture is an especially popular profession for sensitive male characters in films whose plot demands upper middle class lifestyles and creative personalities. (The devoted widower, architect Tom Hanks, in Sleepless in Seattle.) Architects can be molded to be romantically idealistic and underemployed (early Rourke), or dangerously committed and overworked (Richard Gear in Intersection, Jeff Bridges in Fearless, David Strathairn in The River Wild.)

The greatest scorn is reserved for interior designers, especially interior decorators from Los Angeles. Interior designers are repeatedly represented as vain, thoughtless, artificial or hopelessly shallow charlatans exploiting the whimsy of rich, bored housewives. (Richard Gere masquerades as a gay decorator in American Gigolo to avoid detection of his actual profession. The outrageously self-absorbed New York nouveau riche designer destroying with ludicrous post-modern home “improvements,” a quaint, authentic country house in Beetlejuice.) Post-modern decorating is the visual manifestation of the fast money and conspicuous consumption that has come to represent the go-go ‘80s, the decade of greed Daryl Hannah as the decorator/girlfriend of Charlie Sheen? in Wall Street.

Certain conditions of design work can also be useful in plot construction. For instance, designers can work at home (allowing for all kinds of narrative possibilities; e.g. Lange in Cape Fear terroized by DeNiro) or at a photogenic office: exotic flower arrangements, severe angles, modern art, white walls. (Architect Wesley Snipes and secretary Annabella Sciorra’s scene atop the pristine drawing board in Jungle Fevergave a whole new meaning to the phrase “graphic sex.”) Designers have flexible hours (no dying patients back at the hospital which facilitates long lunches and afternoon trysts), wear unusual or eye catching get-ups (showcasing the costume designer,) and live in funky lofts and picturesque parts of town (good location possibilities.)

The commercial arts career – like that of interior decorator and gallery director – is especially suitable for the professional female character that demands a job but cannot appear too hard-edged (doctor, lawyer, architect) or too much of a throw-back (housewife, teacher, nurse.) Television commercials have relied on the female designer as a staple character. Countless women professionals with countless pairs of pounding temples rotate in their ergonomic drafting chairs away from white drawing tables speckled with pens and brushes to reach for an aspirin/Anacin/Tylenol. The harried female designer joins the architect in a hard-hat inspecting the construction site, the creative director with boards and easel finessing a presentation, the industrial designer squinting at a wire frame model on a CAD screen, in the stock of commercial images.

Yet despite the creative types that dot the mediascape, the design profession remains almost completely invisible. If it is true that only 2% of American adults understand what a designer does, its not surprising that it is so rarely present in popular images. The few that do appear tend to be the butt of a joke; the arty, affected characters that are eventually revealed for their true, shallow little selves. Design by its very nature disappears into the texture of the world around us. As ridiculous as it may sound, we have no designer role models. As skewed an image as it was, Howard Rourke at least caught the imagination of the audience, projected an image that design could be a hopeful, powerful act. But don’t despair, The Fountainhead has been optioned for a remake, first by Michael Cimino (The Deer Hunter), now by Barry Levinson (Bugsy). So it only a matter of time before the myth gets recharged nineties style: Howard Rourke, the heroic proponent of deconstruction, bucking the committees of sniveling, compromising, modernist swine.

© Michael Rock