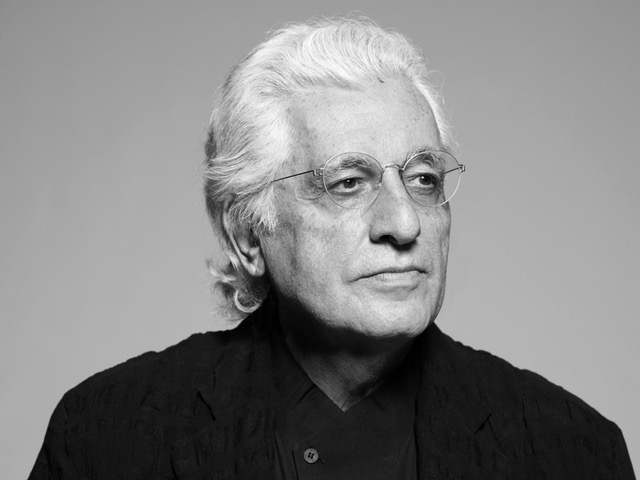

Photo courtesy of Chiara Costa

The day after his death, as many of his friends and colleagues were sharing dismayed memories triggered by sudden, inexplicable lost, Chiara Costa sent me a blurry snapshot from the installation of the exhibition Art or Sound at Ca’ Corner della Regina in Venice: it’s Germano and me, shot from the back, doubled over in laughter. While I had no memory of the exact object of our amusement, I immediately recognized the sentiment. When you worked with Germano – despite the creative intensity, the grueling hours, the all-nighters, the last-minute glitches, and the hair-raising complexities of handling precious objects – you laughed a lot.

You laughed, I think, because Germano’s love of the work, deep knowledge of the things, and incomparable experience in creating experiences, was built on an all-encompassing embrace of the uncontrollable happenstance of life. Such an openness to inevitability was liberating: the overriding sense that everything would somehow, improbably, work out okay in the end. That marvelous receptivity was juvenile, that is characteristic of youth, as it was supremely optimistic. I’d like to say Germano was a father figure – he’s perfect for the part – but while he had twenty years on me, he always felt younger, more nimble, irreverent, and playful than I.

That liveliness was in itself instructive and working beside him imparted a continuous stream of lessons, often framed as the metaphors by which he ordered his process. He was most in his element stalking a gallery littered with art and crates and ladders and workers, scanning the walls as he strategized his chess game: the delicate, strategic act of putting objects together in space in ways that multiplied and extended their power and significance. He would rearrange page layouts, often scribbling diagrams in the margins or attacking them with an outsized pair of scissors, as he composed his rivers: free-flowing streams of words and pictures that carried the reader along from island to island never forgetting the significance of the journey between them. The goal was controlled chaos – a barrage of experience coming from every direction – but if you went too far, if you lost control, you risked the ultimate admonition, the casino: a cacophony of spectacular yet incoherent effects organized without purpose.

For me, that was one of the delicate aspects of the way Germano operated. He seemed to know just how far to push things and when to pull back. While he was notoriously adventurous with installation, he’d often review our proposals, embracing some but rejecting the ones where the design overreached. “Not this one, it’s a work,” he would caution, meaning it created a confusion between the object and context: we were cluttering the message. But just as often he would be willing to take the risk, to try something new and untested, with the hope of inventing something. “Vediamo,” let’s see, meant the proof was only in the trying and the looking. Go for it.

What more could you ask for in a creative collaborator: an organic intellectual, a tough critic, a pragmatic realist, and lenient enabler rolled into one. He was a consummate partner, assertive but always open to contributions from his tight teams of artists, co-curators, designers, art handlers, and craftspeople. When asked how he was so prolific, he would always respond, “You have to have your team.” He orchestrated an incredibly loyal band around him, in our studio as well as his own – Astrid, Chiara, Mario, Sung, Alessia, Marcella, Filippo, Chris, Francesca, Gala, Yoonjai, Liliana, Donnie, and the list goes on and on – and trusted them enough to know when to leave the scene for a few hours, or a few days, and let work develop. Absence, he told me, is sometimes just as productive as presence. But beyond his enormous professional, intellectual, and curatorial achievements, what really set Germano apart for me was his kindness, warmth, and generosity. When visiting our studio, he never failed to acknowledge the lowest member of the crew, to consider the proposal from the intern, to take consultation from the receptionist.

A few weeks ago, Germano stopped by our studio for the last time, just before he headed back to Milan. As usual we had an assembly-line meeting, moving from one project to the next: checking on the status of two catalogues already at the printers, looking at layouts for a vast new book we were developing, kicking off a hugely ambitious new series of exhibitions and symposia, and speculating on another equally far-reaching project on the horizon. He was, as always, totally on: charming, funny, intellectually engaged, constructively critical and laudatory in equal measure. As usual he took a moment to personally greet and enthusiastically acknowledge each of the teammates. As we parted, we touched elbows, the new handshake, and laughed about the improbability of it all, this crazy new-normal that was just dawning on us. I remember being, once again, in awe of his energy. We made a date to meet in Milan a few weeks later, then he was off, back out into the city, off to the next adventure. Somehow everything would work out ok. That’s the last I saw of him.

Photo courtesy of Brigitte Lacombe